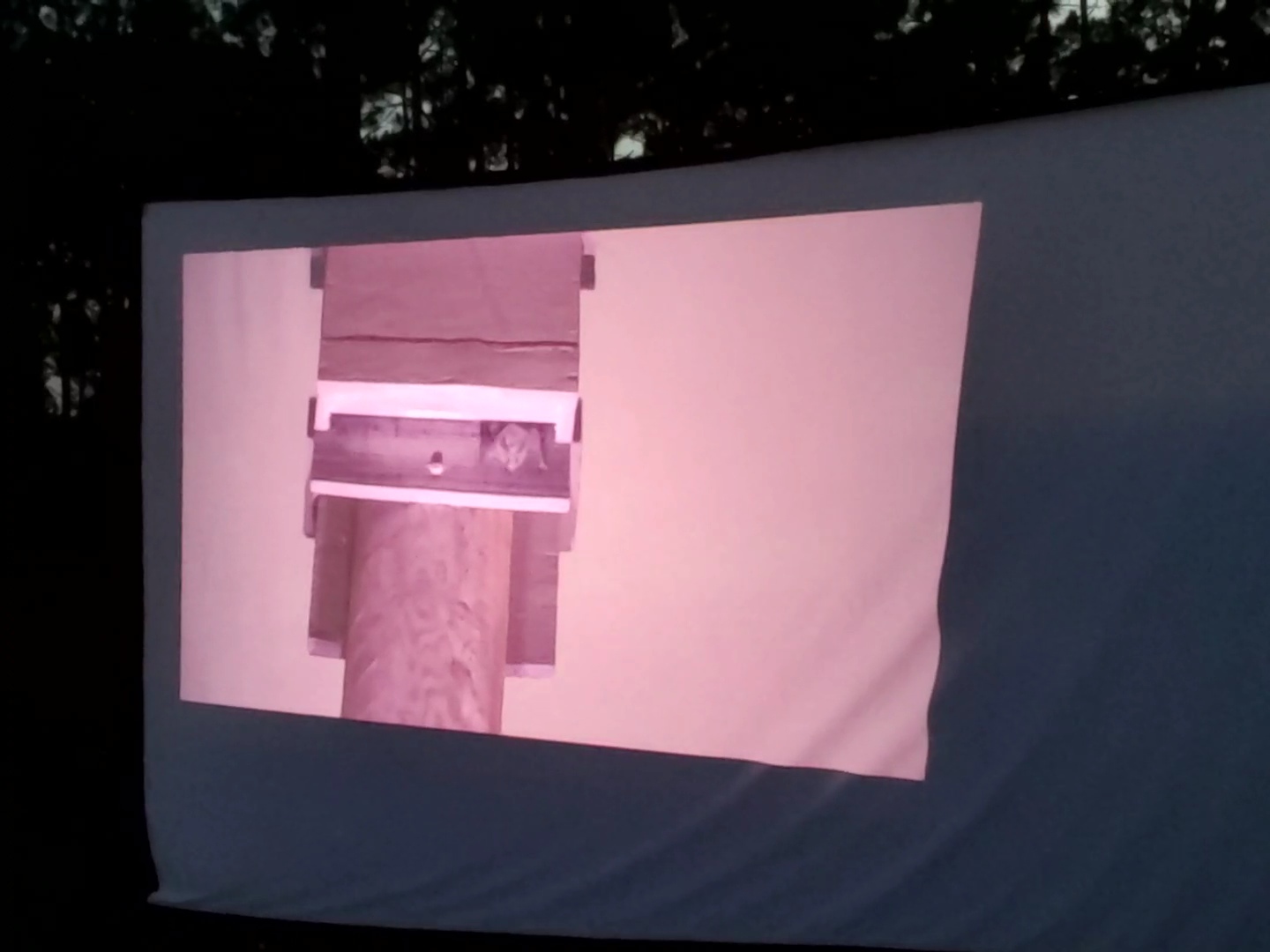

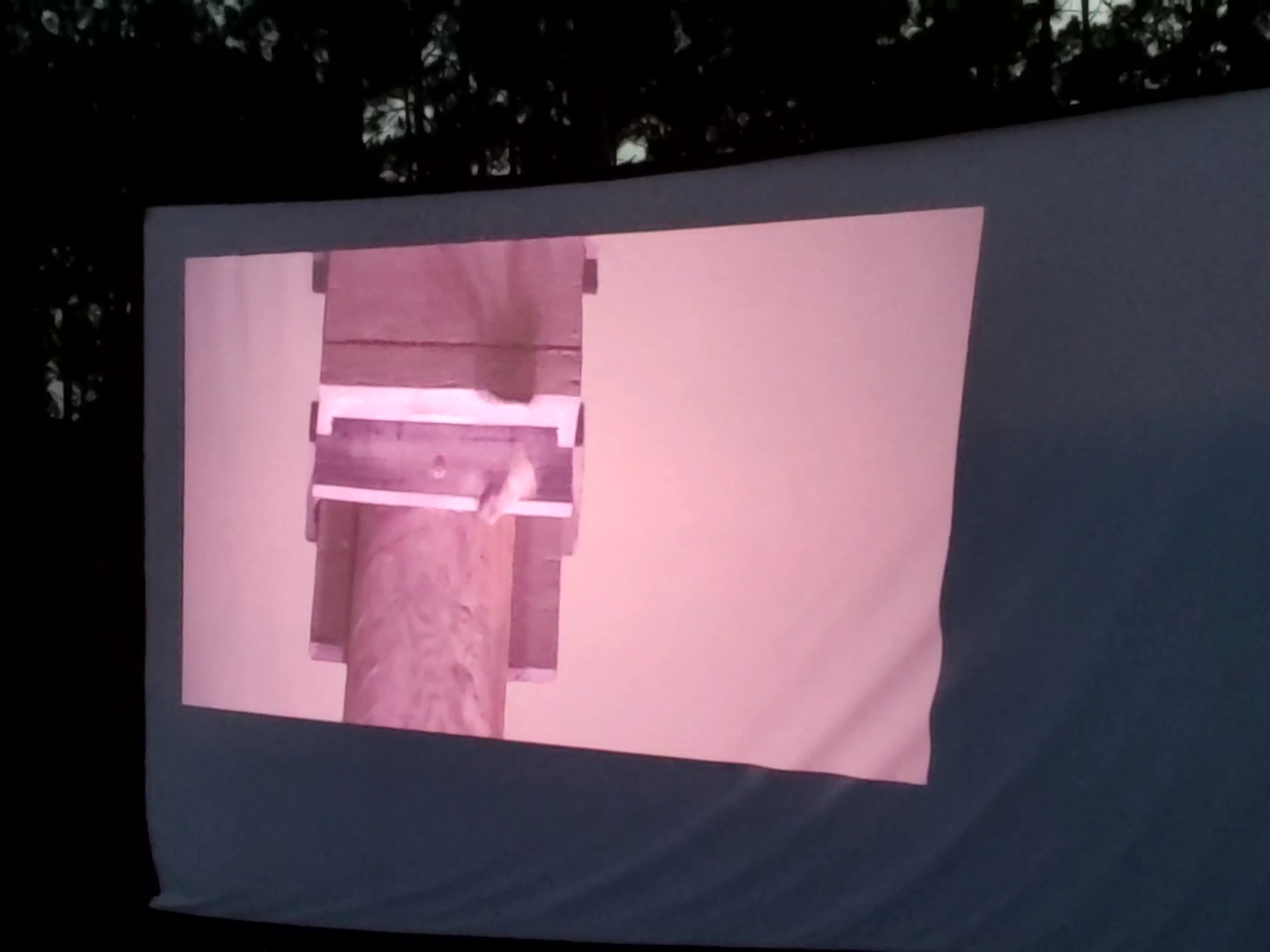

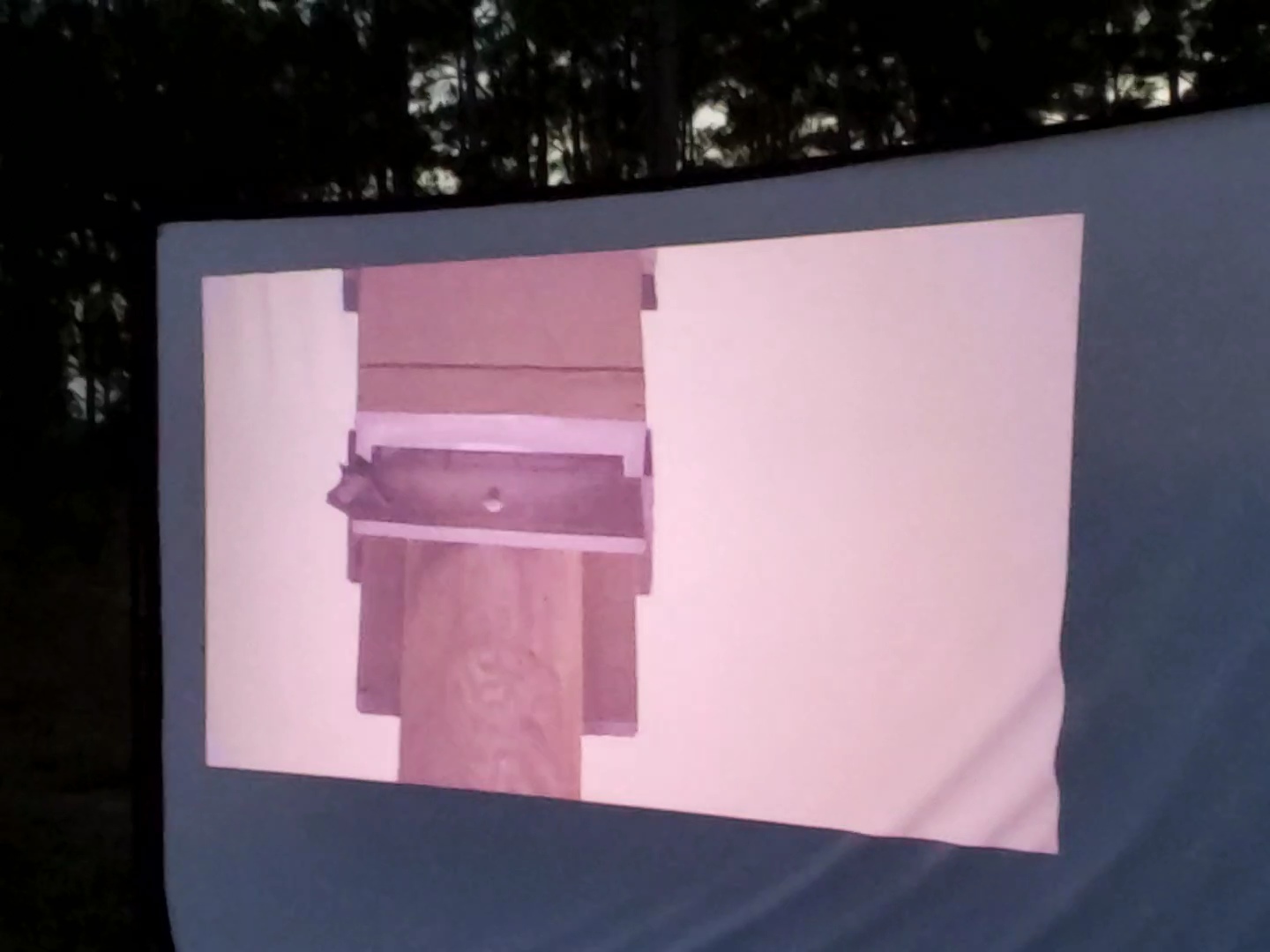

It’s the first day of June. It’s unseasonably cool for a south Florida evening this time of year. In front of us all is a tall pole with a small box affixed to the top. In front of that is a special camera wired to a projector showing a close-up of the box on a screen stretched over a work truck. A group of biologists are chatting amongst each other, all waiting for the sun to set. As dusk approaches, they are reminded to keep quiet so our guests are not startled from making an appearance. In near silence, we wait as the bugs begin to show. Standing for the better part of an hour and a half and swatting away the pests was not the easiest task. The anticipation made it feel like an eternity. Finally, some activity is noted, making it all worthwhile.

Mobile devices start chirping. The chatter begins again, in whispers this time. “They’re waking up!” someone whispers excitedly. Moments later, a tiny figure appears on the screen. Just as quickly as everyone gasps, it takes to the skies and darts just a few feet over our heads. It takes a hard left and disappears into the night, starting its foraging routine. Several minutes later, another emerges, followed by another several moments later. Only a few showed up, and only for a moment each. But it’s something the biologists will remember for a lifetime, this one in particular.

It happens so quickly, it’s easy to miss. I attempted to grab a couple photos of it happening. Most chose to emerge directly from the box opening; however, one decided to crawl around on the outside of the box before dropping off and taking flight.

So what made this such a memorable experience? The tiny creatures in question were Florida bonneted bats (Eumops floridanus). If you look closely enough, bats can be seen just about anywhere darting across the dusk sky. But these guys are different. Not only is this the most endangered and largest bat in Florida, it is the most endangered mammal in all of North America. With fewer than 1,000 estimated to exist in the wild, it is a distinct pleasure to witness one, even from afar for such a short period of time.

The genus is derived from the Greek eu meaning “good” and mops meaning “bat” (much nicer than the Tadarida I’ve mentioned before which, apparently, translates to “withered toad”), with the species name clearly referring to the fact that it only occurs in Florida. In fact, like the crested caracara from my earlier post, this bat is limited to a very specific range within Florida. Furthermore, their habitat is prime land for developers. Through acoustic monitoring and roost surveys, we do our best to make sure that habitat that is actively being used is not disturbed. However, unfortunately, if the land has been determined not to be currently under heavy use by the species, it can be developed. This is an unfortunate necessity for progress that also might possibly hinder the expansion of certain populations that I personally hope will be investigated in the future.

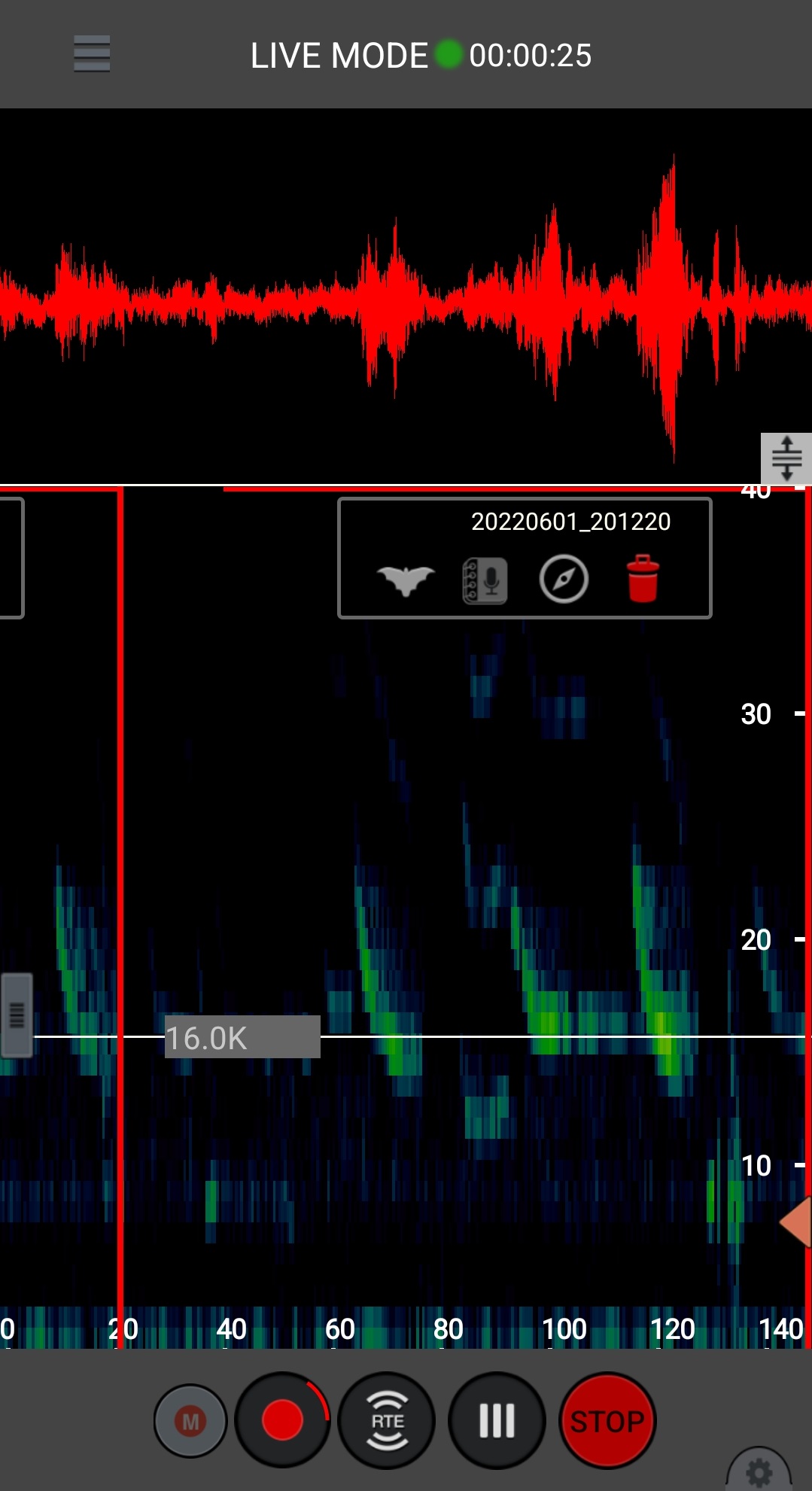

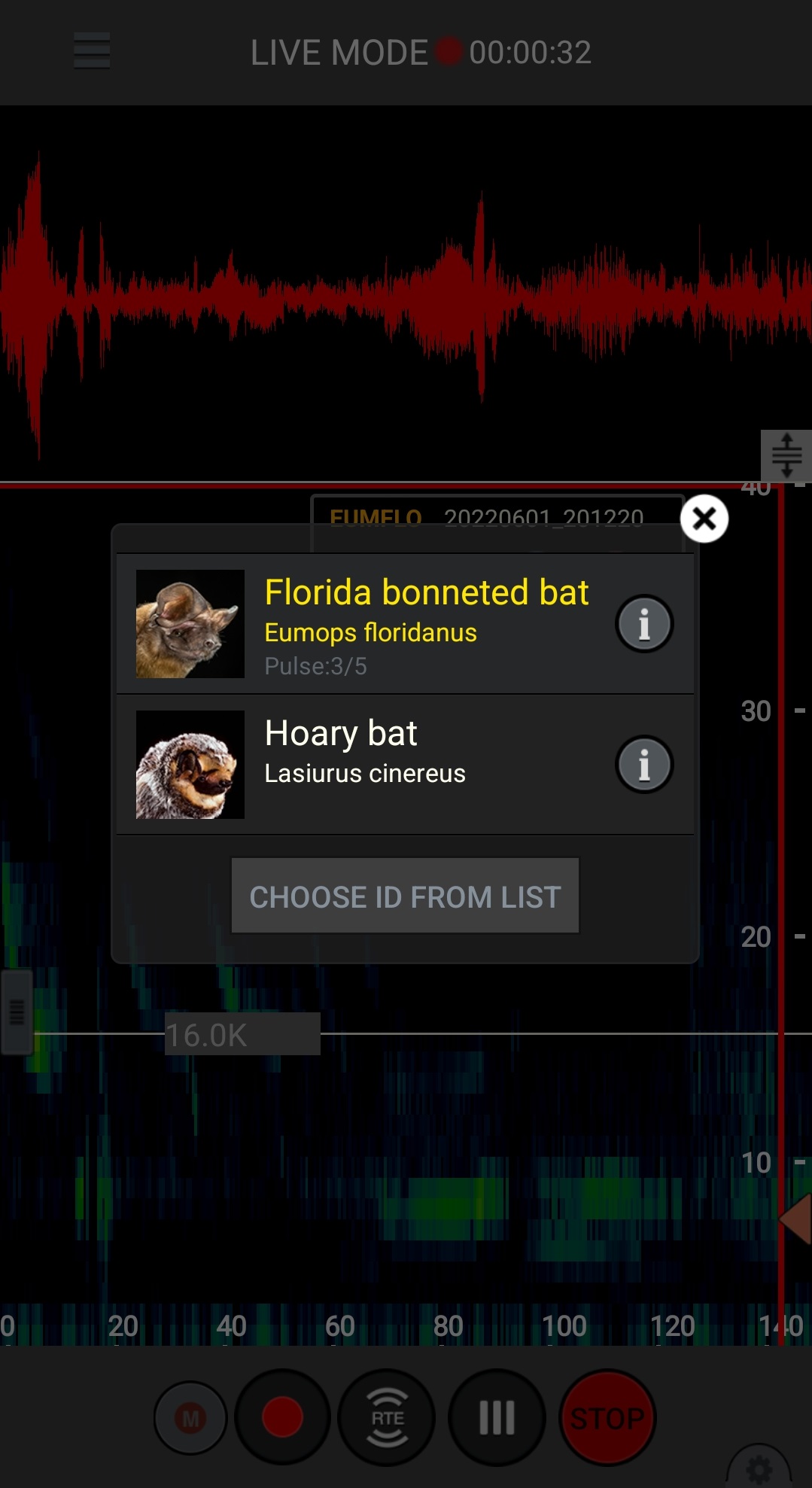

But I digress back to the emergence. If it wasn’t exciting enough to be able to see these animals, if only for a moment, we actually got to hear them as well. Thanks to some very interesting equipment from Wildlife Acoustics, we were able to use our phones and other devices to both hear and see their calls. A small microphone that plugs into the charging port of a device picks up their calls and a free app transforms them into something that can be seen visually. In addition, the program can adjust the frequency to a level that can be heard by humans and makes an attempt to identify the bat species based on the calls.

The visual representation in the app is a much coarser version of what is provided by the software that we use for our surveys. We set up detectors with microphones programmed to “listen” for bat calls during the night. The detector takes audio recordings which are then run through the software to produce visual representations of the calls. It also provides quantified details of each call, such as the slope and duration, which we can analyze to tell if the call came from the species indicated by the software. The screenshot below is of one of the best Florida bonneted bat calls I’ve seen from one of our surveys.

The width of the red oscillograms at the top, as well as the intensity of the colors in the calls below indicate the “loudness” of the sounds. You can see here that their calls start off very powerful and taper off towards the end. You may think it takes a very specialized microphone to hear something that is so quiet that we can’t even hear it. Well, you’d be partially correct. These microphones are specialized. However, they are specialized to be able to pick up the very high frequencies of bat calls. Their calls are anything but quiet. I’ve read that bat calls can reach 110 decibels and that that is equivalent to holding a beeping smoke detector four inches from your ear (Bats of Florida, Marks 2006, pg. 32). At 10-20kHz, the frequency of the Florida bonneted bat is low enough that, if you listen very carefully, you can actually hear it unaided (although the ability to hear at this frequency dwindles with age). Most bat calls are well above the frequency at which humans can hear, such as with this southeastern myotis (Myotis austroriparius), whose calls are in the 40-70kHz range. You can see how this call is quite different from that of the Florida bonneted. Not only is it more powerful at the end, but the range of frequencies in which it falls (known as “bandwidth”) is much wider as well.

This post didn’t include as many pretty pictures as usual. But I hope it shows the unseen beauty of these animals. People think we as humans are amazing because we can talk, build tall buildings, invent things, etc. But imagine having to basically scream at your surroundings and interpret the echoes, sometimes hundreds of times per second, in order to see and hunt, all the while flying by using the skin between your arms and fingers. Sure they are cute (at least to many of us), but it’s the little unseen things that I think make them truly amazing.

I don’t usually do “credits” at the end of a post, but this incredible experience would not have been possible without the help of Zoo Miami, The Miami Bat Lab, Wildlife Acoustics, and the FWC. Many thanks to them!