As I learn more, find more, and visit more places, there may be future parts to my seashell adventures. But I definitely wanted to separate the first couple since the world of bivalves takes up most of it. There are a couple of other categories of animals that can produce the shells that so many of us enjoy. This first one may come as a surprise as far as the type of creature it is. Additionally, while it may be familiar to most, a deep look into the structure itself is likely going to surprise you and hopefully give you an even higher appreciation for this unique shell.

This is the common sand dollar (Echinarachnius parma). When researching the scientific name, I didn’t come up with much other than the fact there is a parma wallaby whose name origin is also a mystery. I do know that the first part of the genus, echin-, refers to the living creature having short spines all over its body. That’s the part that some people are surprised about when it comes to sand dollars. They are technically sea urchins. While we usually think of urchins having long spines that could stick you, the sand dollar has numerous, very small spines that give it sort of a fuzzy look. These spines fall off readily upon the death of the animal. It is very important to know whether a sand dollar is alive or dead as collecting a live one just for a decoration is not only unethical, but in many cases illegal.

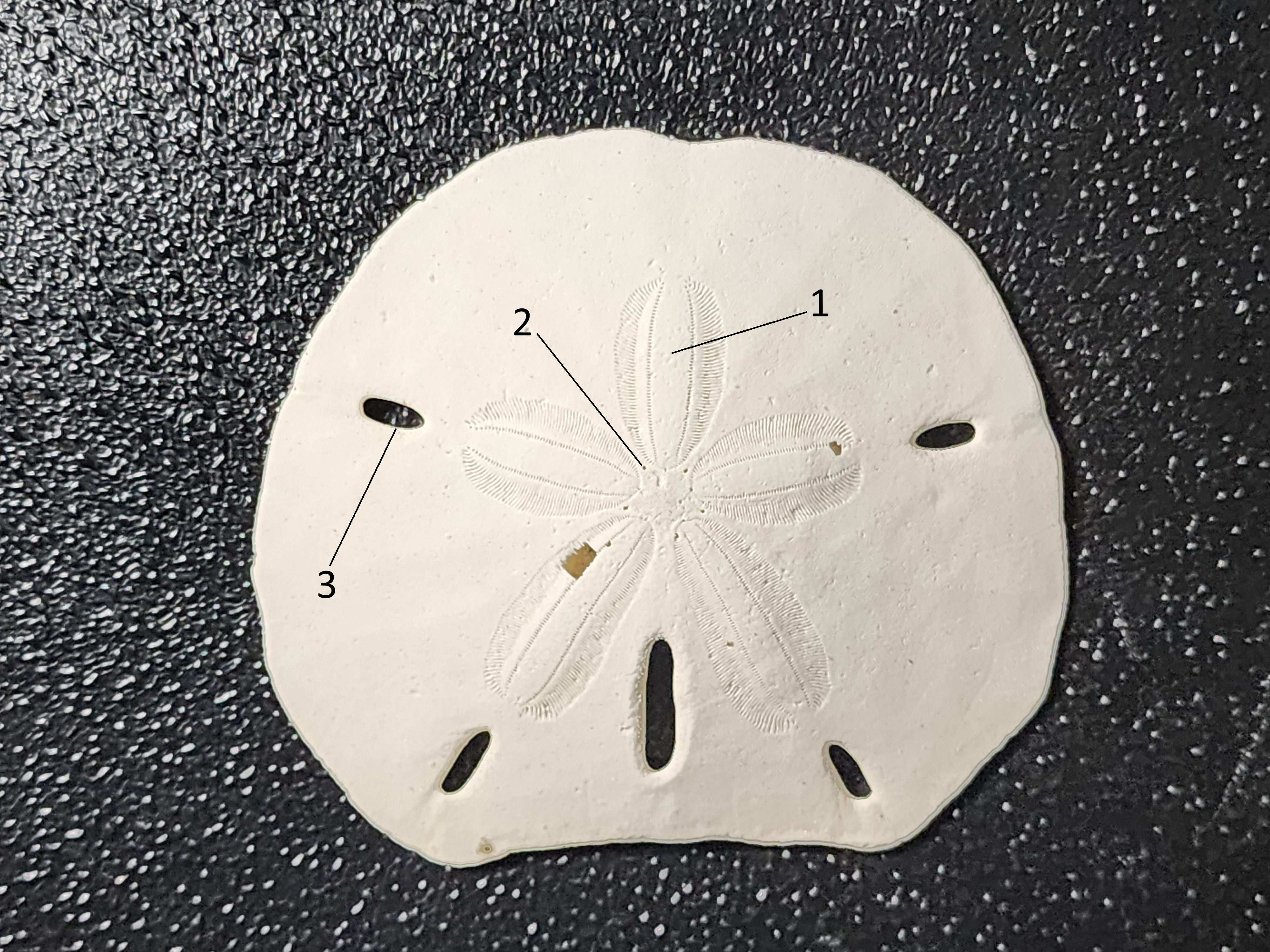

While the look of a sand dollar may be common, especially in Florida, the anatomy that can be viewed just from the shell is something that I personally find fascinating. First, the familiar view from the top. That “flower than you see isn’t just for show. These are known as “ambulacra” where tube feet are located which helps with gas exchange (1). Once a sand dollar has dies, and especially as the shell bleaches in the sun, it becomes very brittle. As a result, there are a couple of divots and holes in the one I found. However, there are some functioning holes as well. The five tiny holes on the tips of the “star” in the middle are known as “gonopores” from which sperm or eggs would be released during fertilization (2). The star itself is known as the “madreporite”, which is where water is brought into the water vascular system (something I could write an entire post on just by itself). The small openings are known as “lunules” and provide for a stronger structure and allow water and sand to pass through. This prevents the structure from acting almost like a hard parachute, which could injure the animal in turbulent waters (3).

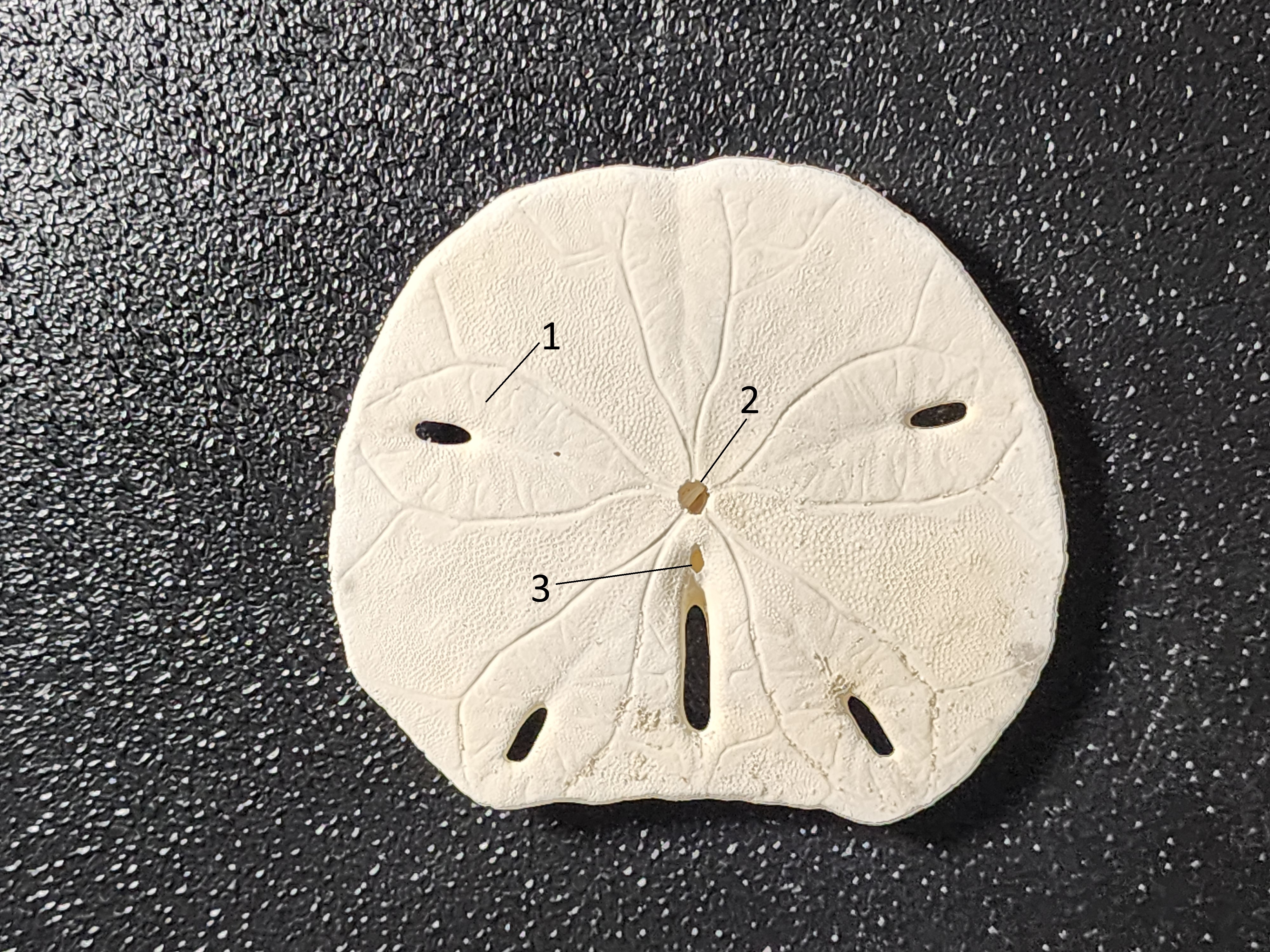

The underside of a sand dollar, for decorative purposes, may not be as attractive. However, a lot more can be learned about how the animal eats. Here we see another flower pattern. Each “petal” is called a “food groove” in which cilia and tube feet guide food particles toward the mouth (1). The mouth itself is located in the central opening (2). Just below this, you can see another smaller opening that is…well…in very unscientific terms…that’s its butt (3).

The remaining shells in this post belong to a group of animals called “gastropods”. The word comes from the Greek gaster meaning stomach, and pous meaning foot. This is in reference to the “foot” of the animal basically being an extension of the rest of the organs. Gastropods basically include snails and slugs, although I’ve learned through my new obsession with shells that “snails” do not always take on the form you would expect.

This first shell is not very interesting to look at, but the animal it came from is quite fascinating. This is what’s left of the shell of a wormsnail (Vermicularia spp.). There are two species of wormsnail that these could have come from – the West Indian wormsnail (V. spirata) or the Florida wormsnail (V. knorii). This is showing just the business end of the shell. The other end would be more tightly spiraled, like you would expect of a snail shell, and would have the features needed to identify to the species level. These snails attach themselves to coral or sponges and feed using cilia that protrude out and produce a mucous net that catches plankton, a feeding strategy known as suspension feeding. They start off more coiled early in life, then uncoil as they grow older.

This next shell is one that I honestly assumed was a bivalve before learning more about it. It looks like the type of shell that could have two halves that come together. However, there is a little compartment within it, which is actually the chamber that holds the animal’s body. This is known as the Atlantic slipper snail (Crepidula fornicata). The genus name is sort of slipper-derived, based on the crepida sandals – the type you picture when you think of ancient Romans. Now, I know what you are probably thinking when it comes to the species name. While it does have roots with the word “fornication”, and, as you’ll see in a bit, this species does have some interesting mating habits, it’s not quite what you think. The Latin fornix means an arch or a vault. In ancient Rome, prostitutes would meet their clients under vaulted ceilings, making the word “fornix” a euphemism for a brothel. However, when it comes to slipper snails, it is in reference to the arch that they form when mating.

The strangest part of this reproductive behavior is that they practice something called sequential hermaphroditism. Anytime a slipper snail arrives on the substrate on which it will live – rock, coral, etc., it is a male. However, when another snail arrives and attaches itself, the first one becomes a female, and the new one assumes the male role. As more snails are added to the stack, this continues so that the snail on top is always a male, and all the rest are females.

This next shell belongs to an animal you may have seen before and passed right by it thinking it was a barnacle. This is known as a keyhole limpet. Specifically, based on every other radial rib being a different size (impossible to tell from the photo), I believe these to be from Lister’s keyhole limpets (Diodora listeri). Despite their small size and nearly sessile nature, they play a very important role in the marine ecosystem as they control algae on rocks in tidal areas. During high tides, they move very slowly across the rocks, feeding. They somehow predict the tides and, before the tides go out, they pick a resting spot where they remain dormant and exposed. The “keyhole” at the apex of the shell is used in the gas exchange process. Water is brought in under the edge of the shell, passes over gills, and exits through this hole.

Now to move on to shells that look a lot more like you’d expect them to. These have more of the spiraled apex with the aperture (opening) one would expect. Although, this first one is a bit odd shaped compared to the others. Rather than having a more rounded aperture, the opening on this shell is more elongated, running down the majority of the body. This interesting species is known as a lettered olive (Americoliva sayana).

Apparently, the darker markings on the shell can sometimes resemble letters which is where it gets the name. Olives are carnivorous and will capture their prey with the muscular foot, then dig down and eat below the ground surface.

This next shell is quite small but has a beautiful, sturdy form (shout out to my intern, Kailanee, for finding this one for me!). This is the shell of an apple murex (Phyllonotus pomum). Despite the small size, murices are efficient predators, subduing their prey with a venom. This venom was also used by Phoenicians to make the dye tyrian purple. This venomous secretion also acts as an antimicrobial lining for the egg masses. These masses are a congregation of egg capsules from many females within a population.

I was very fortunate to have found a larger, intact shell from this next one. This is the unmistakable Florida fighting conch (Strombus alatus). The Latin strombus refers to something that is spun around. The Latin alatus means “winged”. Under normal circumstances, these “fighting” conchs are actually quite peaceful and do not attack other species. However, when two males are competing for a female, they will oftentimes fight each other to the death. The photo below is of an adult fighting conch along with another smaller shell that I found. I wasn’t able to identify it as any of the smaller species, which makes me wonder if it might be a juvenile.

I saved my favorite for last. Again, I have yet to find a larger specimen since only broken fragments of those typically make it to shore. This is the shell of a lightning whelk (Sinistrofulgur sisistrum).

The scientific name makes it sound very…well…sinister. And like with the slipper snails, there is a common root word there. The Latin sinister refers to something being on the left side. There is also a word called “sinistral” that basically means left-handed. And the lightning whelk is one of the only marine snails that is “left-handed”. If you take a snail shell and turn it so the aperture is facing you and the apex is facing up, other shells will have the aperture on the right whereas the lightning welk has it on the left. There are right-handed (dextral) lightning whelks, but they are very rare. Below is a photo of several of my other shells with the lightning whelk, so you can see the difference.

I know this is a bit of a departure from my usual more visually pleasing photos of live animals. But my hope is to inspire anyone walking along our beaches to take a moment and appreciate shells, not just for the decorations they are now, but for the wonderful animals that they once were.